|

|

|

|

September 2008.

After an eight days' foot march – mostly voluntary, as we could also have gone by one of those tiny airplanes and Jeep – we arrive in Jharkot. The last village below the pilgrimage site Mukhtinat and its hostel settlement. Nestling onto a crumbling cliff, towered over by its monastery, its palace ruins and the new community hall. Clay houses with platform roofs and intricately carved window frames from better times, stapled like card houses. Sporadically new concrete buildings at the periphery. |

View from the village towards school and monastery |

Four village wells, water tanks on some of the roofs, other households have to fetch their water from the well in canisters. Solar cookers almost everywhere. Buckwheat, apple slices and turnips put out on the roofs and terraces for drying and stocks of wood: not for heating - no house is heated, only for cooking there are narrow clay ovens with room for two pots and, sometimes, a stove pipe. Showers, even warm water!, in the five hostels, called “hotels”, and in Jharkot Traditional Medical Center School, the small boarding school on the monastery grounds.

There we are going to work for the next three months. |

Dolma warming her hands at the oven

Dolma warming her hands at the oven  |

In the afternoon a warm welcome by Mohan Gurung, the headmaster, project manager, English teacher. Tea in the small consulting room with Amchi Nyima, the Tibetan doctor. Raphaela, volunteer from Germany, 30 years our junior, leads us through the school’s rooms: three sparsely furnished, tidy little bed rooms for the children, one narrow class room with whiteboard, stationary cupboard, four tiny school desks. The rooms of Mohan Gurung and Tsering Dolkar – teacher for Tibetan –also frequently used for classes. In the cook’s room, sacks with rice and Tsampa, canisters of cooking oil next to his narrow bed. The kitchen with the typical wood-devouring clay oven and a gas cooker, a pile of four low tables which is deconstructed three times a day for mealtimes. |

| The prayer room with its rows of narrow mattresses along its sides and a shrine at the front wall. Here also classes are held every now and again, but now the 14 children of the school are sitting there cross-legged and with folded hands and recite the Tibetan texts of their daily Evening Puja, - Evening "Prayer" would be an altogether insufficient translation: as so much energy and intensity the whole congregation of an Austrian village could not muster. Chanting rhythmically, alternating slow and fast sections, a kind of sprechgesang with an unfamiliar tone colour, sometimes accompanied by clapping hands. Who becomes sleepy nonetheless gets up and spends the rest of the Puja incessantly prostrating in front of the shrine. The whole thing takes about half an hour, then the children have warm hands and feet whereas we onlookers are freezingly cold despite our down jackets. |

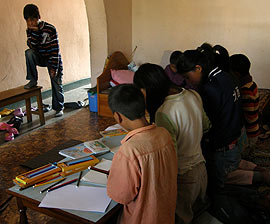

| We have brought material for painting and handicraft. Coloured paper, water colours, oil pastels, scissors, glue. The children love the classes: The improvised gong is beaten, "Class two and three - English lesson in the prayer room!" or even better: "Drawing lesson!" They rush over, pull us into the room, drag the low tables out of the kitchen. We are not allowed to do anything ourselves, they fetch our bags from the courtyard, paper and paints from the classroom and button up our jackets. If the programme allows the classes are held in the open air, in the sun outside it is warmer than inside, even in the middle of November. |

Pema Dechen designing a paper mask Pema Dechen designing a paper mask |

| The children do still life studies, they draw cartoons and portraits, they learn to work with brush and tempera paint, they paint feelings and dragons, they build model stone houses, they make mobiles and masks out of paper, rattles out of broken light bulbs, they decorate their rooms. Even a short theatre play is performed in front of a small audience.

In the children’s daily lives there is a clear assignment of duties: each of the three rooms which sleep five children each, sometimes two to a bed, has its own "captain" who is responsible for its tidiness. Every day two different children do the dishwashing, two more serve the meals. You never see them quarrel whose turn it might be, they are never in a bad mood because of their work. |

|

Food is eaten in two separate groups because there is hardly enough space in the kitchen for all of them. The meals are simple, there is a menu which is repeated every week. In any case there is Daal Bhat for lunch every day – rice, lentil soup, some vegetables. Of the latter there is a moderate variety: sometimes green beans, sometimes cauliflower, sometimes chard. From November there’s only potatoes and kale. You eat with your fingers, and even we spoilt westerners become almost addicted and order our daily Daal Bhat in the hotel on our days off... |

| For breakfast Rishikant the cook sometimes makes piles of Chapatti bread on which the children spread peanut butter and cheap jam. Delicious are the Ting Momos – spirals of steamed dough – or the vegetable-stuffed Momos which are sometimes served in the evenings: and because one alone cannot manage making the required several hundreds of them, some of the children cancel their evening prayers on such evenings . In the kitchen cook, children, teachers, westerners, the Amchi and one monk or the other work together harmoniously, roll out the dough, cut out circles with a drinking glass and stuff vegetables in them, and shape – well, Momos. |

Filling Momos ...  |

You can see who’s made which, the complicated, the pretty croissant-shaped ones with the curly hem only experts can manage. We’re joking in three languages; it smells of wood fire in the oven and we are happy.

We are happy, and we are lucky: it is an exceedingly friendly, warm autumn this year, but it still gets colder every day. The first villagers move to the lowlands to pass the winter at relatives’ places, up here there are several degrees below zero at night but no heating. On the 20th of November the Medical Center School closes down as does the public school of the village. |

| But whereas the latter releases its students for three months of uncomfortably cold holidays ours will meet again in Pokhara after a three weeks` break and will continue their classes there until the middle of March. Mohan has managed to find an affordable quarter for the winter school. He has gone ahead down there to prepare everything, the children walk back to their home villages to be with their families, and Wolf and I walk to Dzong. We have fallen in love with the little monastery on the other side of the canyon, and the abbot there has enthusiastically accepted our offer to teach the eleven child monks for a week. It turns out to be an unbelievably intense, hard, beautiful week – but this would require a report of its own. |

| It isn’t easy to say goodbye to Jharkot and its people. We’ve sent our heavy backpacks ahead to Jomsom on horseback and the two of us walk down to Jomsom on foot. You just cannot drive away from up there by Jeep, you have to consciously feel this landscape when leaving. Then a breath-taking flight in a tiny airplane through the valley of Kali Gandaki takes us from Jomsom to Pokhara. |

A glance back into the Kali Gandaki Valley A glance back into the Kali Gandaki Valley |

Winter School in Pokhara. December 2008

There are 10 days left until our departure, which we will spend in the school’s winter quarter: five rooms and a small kitchen in a private house. The children, Mohan, Dolkar, the cook and his wife, Sri Kanter (the Nepali teacher) and the two of us: that’s 21 people on approximately 80sqm. The owners have crammed their furniture and themselves into a room upstairs, we share staircase, washing basin and toilet with them. The shower as well - it mustn’t be used though, as the water in the tank wouldn’t be sufficient for so many people. |

Laundry and personal hygiene is done in the nearby river: this is truly thrilling for the children who can flounder about in the water for the first time in their lives, and we enjoy it as well.

We are privileged by the way: Wolf and I have a tiny room with proper beds to ourselves, the other teachers and the cook sleep in the children’s rooms. And Mohan’s room is used as dining room – so there is almost no privacy. |

|

In the beginning there are only twelve of the 14 children here – Bhujung and Ngawang Tsering are missing. Insistently Mohan tries to contact their parents and finally succeeds with the help of some people from Jharkot and the children´s home villages. There is no money for the journey so it is sponsored, and when the two boys finally arrive after several days there is happy excitement. At once the newcomers are ushered into our room by their roommates: they haven’t yet received their photos which we have printed in the meantime and also their new paint-boxes!

The classes continue, we have organized more material and especially work on making the rooms more homelike with simple means. Whereas the other subjects are taught in the sleeping rooms or on the terrace our art lessons take place in the “big" room, open to the hallway. |

Arts lesson in the winter quarter  |

The children kneel on the thin mattresses which serve as beds at night, two low tables are our desks. Occasionally there are people in the hallway all of a sudden who curiously watch what we are doing: acquaintances of the house owners or guests of the tiny restaurant on the ground floor who have heard that something is happening up here.

Due to an influenzal infection I’m temporarily only partly available and stay back with the children when Wolf, Dolkar and Mohan go for a bulk purchase: We have brought money with us donated by students of the Musisches Gymnasium Salzburg. |

There are things needed for simple housekeeping: containers for the toothbrushes, rechargeable lamps for the daily power cuts (eight to twelve hours per day!), sheets, pillow cases, warm blankets, but also underwear, shoes... They come back with two taxis, and unload box after box. Still there is quite a bit of money left and we consult with Mohan and Dolkar on which improvements it should be spent: mainly for better equipment of the school up in Jharkot.

On our last Saturday – which is Sunday hereabouts, so to speak – there is an outing to the Peace Stoupa above Pokhara. All the way up there I walk with at least one child by each hand, Dolma is slowing down considerably as well and hangs on to me heavily. Her heel has become raw, plaster doesn’t help much. Sonam Wangdu, one of the bigger boys but still hardly up to my shoulders takes her on his back and carries her a good part up the steep ascent... |

Karma Choesang on stage

Karma Choesang on stage  |

At the top there we have a picnic, all of us sitting in a circle, actually our tin bowls have come up with us, and the cook dealing out lukewarm Chana (chickpea casserole), hard boiled eggs, tangerines. Then the children show off their acrobatic skills to us: cartwheels, flic-flacs with one or two hands.

Back down again we want to show them the waterfall – Devis Falls. In September still a steaming, roaring hell of water, fed by the abating monsoon, now a friendly runlet in mossy stone cauldrons. |

| More exciting for the children is the well with the statue of the deity Manakamana, the wish-fulfilling goddess, under the water surface. You have to throw in a coin, and if it settles on the statue this means your wish will come true. All our coins tumble down into the impermeable depths out of which, and that’s a real joy, five frogs surface one after the other, floating about lazily. |

Even though Manakamana has not caught our coins: we won’t let anything keep us from fulfilling our own wish to return here at some point in time. We are absolutely positive about this when we bid our farewells in front of the house in the early morning mist one week before Christmas.

For the time being. |

|

Summa summarum

Now, a good month after our return that time in Nepal still echoes within us, still we feel deeply connected with the people we’ve learned to love there.

|

Tsering Dolkar, the Tibetan teacher cares not only for spruceness the Tibetan teacher cares not only for spruceness |

The consistently positive atmosphere in the school, borne by mutual goodwill, tolerance and helpfulness, is surely owed to the two full-time teachers Mohan Gurung and Tsering Dolkar. You feel at once that they love their children and are loved by them in return, and the children act similarly responsibly and lovingly amongst themselves.

Very rarely there are conflicts - which are quickly solved by the help of grown-ups, if need be. In fact, the school is like an extended family, so there is no need for homesickness to get hold of the children who are often separated from their parents for months. These are happy children. |

| Actually it is quite easy to work with them. They are open-minded, enthusiastic, eager to learn, polite. They trust in the teachings of their grown-ups. It is not at all difficult to motivate them since they are not picky; their extracurricular life is, as opposed to ours at home, not (yet) distorted by a flood of ceaselessly distracting impulses. The children – even the youngest ones, 5-6 years old, learn to read and write in three languages already: Tibetan (which is more or less the standard language of their local dialect), Nepali (the national language) and English. This means oodles of vocabulary and three totally different grammar systems. And each language has its own lettering. |

Stone architecture  |

Their learning strategy is very different to ours; they learn by imitation and patient repetition of their teachers’ demonstrations. Independent, creative work – of major importance to us – is not in much demand. We don’t mean to say that the western approach is superior – but we have the impression that a combination of the two approaches could be ideal for learning: The patience for imprinting learning matters in one’s mind - which our students often lack - combined with the ability of creatively applying of what one has learned and experienced. |

| Much to our delight the children, who in the art classes at first almost exclusively stuck to our suggestions, in the course of the weeks developed more and more originality, joyful with their own ideas and persistent in realising them. These experiences could, even if the children won’t have artistic careers, play an important role in shaping their lives: Someone who has experienced their ability to find autonomous solutions for artistic questions can well transfer this skill to other problems. Being in a situation in which their parents’ traditions can’t be carried on without changing them at least in some way, one has to be able to react creatively to the changing circumstances. |

These children will have to face the task of finding their own ways in order not to give up their roots by simply adopting western ways to live and think.

The basic concept of Medical Center School points in this direction: apart from the high quality education with a strong focus on English language an emphasis is put on communicating the cultural heritage – especially the traditional Tibetan medicine and Tibetan language |

|

| One more living picture: On the school’s flat roof with its view over the whole valley the school committee has a meeting. Eight delegates from the neighbouring villages and Mohan, this time backed by Alex Kindler who supports and monitors the project from Kathmandu, Claudia Canz, the chairwoman of the German "Jharkot Projekt e.V." foundation and us two as onlookers. The committee nominates the children who will be accepted to the free of charge school, takes part in the decisions for the school’s development and it is the school’s corporate body after Nepali law. They talk about paving the dusty courtyard, about the as yet unsolved question of contracts for employees, about the necessity of an assistant for the Amchi. |

They talk Nepali so Alex can understand them (and I sometimes get an idea of what they might be talking about). Mohan translates sections into English. Sometimes gusts of wind hit us, noisily activating the tiny wind turbine which provides part of the school’s electric power. It sounds as if the whole building could take off any minute like a heavy air plane and glide away over the valley…

|

During the school committee meeting During the school committee meeting |

| Our three months of living together have made us engaged and involved supporters of this great little school project. We have witnessed the excellent work done there and we hope that these children, wherever their lives will lead them, will figure as small (or even bigger) impulses for a sustainable development of their region, their country.

Christina Klaffinger, Wolf Pichlmüller |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to top |

|

|